The Benefit of the Doubt

The Benefit of the Doubt

By: claycormany in Uncategorized

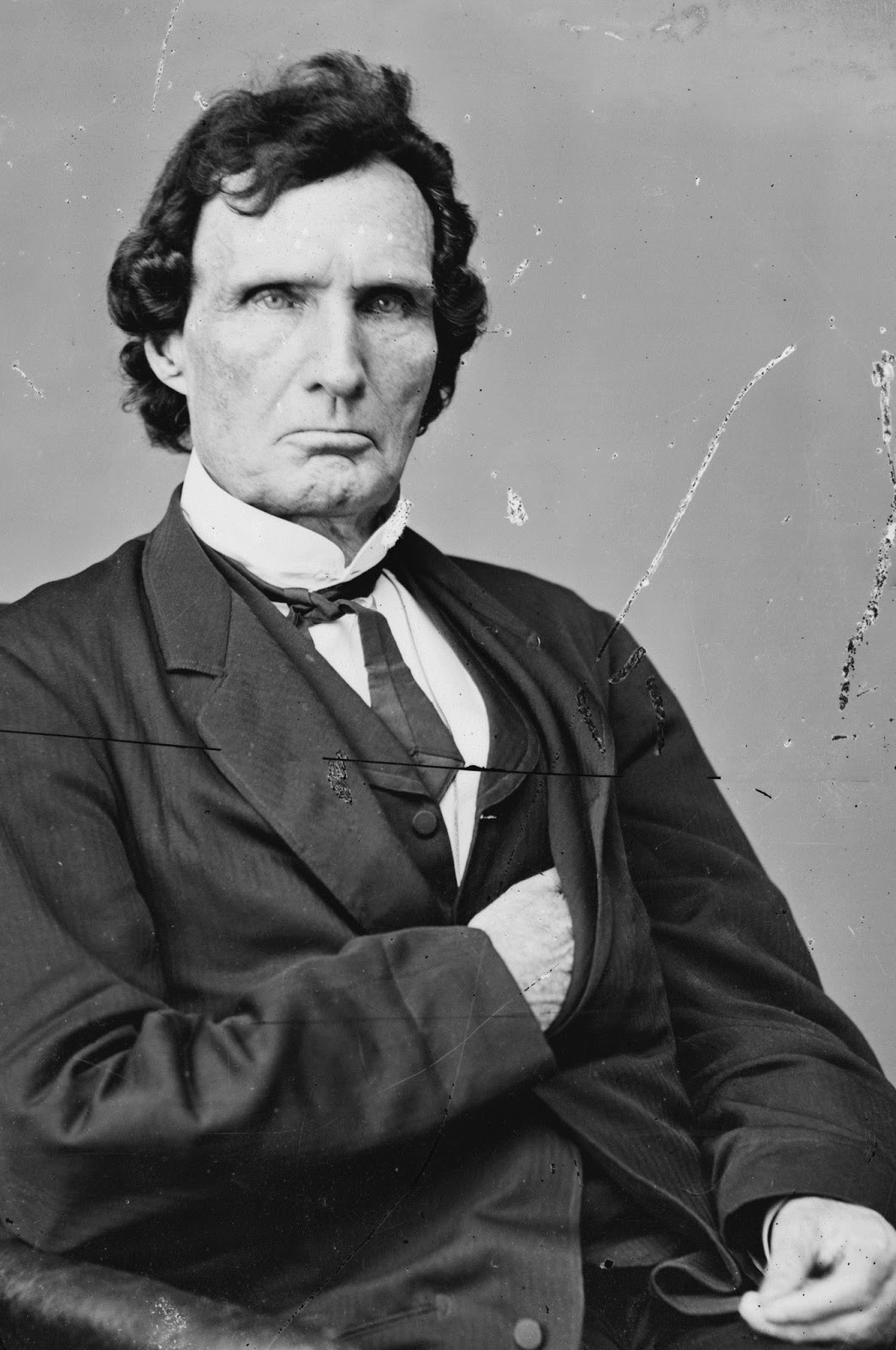

Stephen Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln focuses on Honest Abe’s effort in the early days of 1865 to abolish slavery through the adoption of the 13th Amendment. At the outset, he faced considerable opposition. Even the Radical Republicans, who fervently wanted slavery abolished, were reluctant to help Lincoln, believing his push for the 13th Amendment was a ploy to frighten the Confederate states to rejoin the union before being defeated on the battlefield. “We all know what he’s doing,” exclaims one skeptical congressman. “We can’t offer up abolition’s best legal prayer to his (Lincoln’s) games and tricks.” Radical Republican leader Congressman Thaddeus Stevens (portrayed brilliantly by Tommy Lee Jones) ponders for a moment and then says, “You said we all know what he’ll do. I don’t know, but hasn’t he surprised you?” As he leaves his office, Stevens expresses his intention to work with Lincoln on abolishing slavery, despite “never having trusted the President.”

What Stevens does in this scene is something that is rarely seen in contemporary American politics. He does not presume to know Lincoln’s motivation for pushing ahead with the 13th Amendment at that uncertain time. Instead, he decides to work with him and give him the benefit of the doubt.

The benefit of the doubt. Political opponents seldom grant that to each other these days. Like Stevens’ colleagues, they assume there is something sinister or hypocritical about their opponents’ motives. Or they raise suspicions about someone’s integrity based on his or her association with a discredited individual. The controversy over gun control provides an example of the former. A ban on assault weapons is proposed, and many gun-rights supporters claim (without evidence) proponents of the ban want to start moving toward confiscating their firearms and revoking the Second Amendment. A left-wing news source gave us an example of the latter, when it mentioned a major financial contributor to disgraced New York Congressman George Santos and suggested (again without evidence) that she might have known about the false claims he made regarding his education and work experience.

It can be argued there are high-profile political figures who have been given the benefit of the doubt in the past, and having betrayed the public trust or been otherwise deceitful, no longer deserve the benefit of the doubt. The aforementioned George Santos belongs in this category. However, controversy has recently descended on a Democratic congresswoman and a conservative Christian organization, both of whom, I believe, deserve the benefit of the doubt, at least for now.

A couple of weeks ago, Riley Dowell, the daughter of U.S. Rep. Katherine Clark (D-MA), was arrested during a protest on Boston Common and later charged with de-facing a monument with anti-police slogans and assaulting a police officer. Clark, the House Democratic whip, acknowledged Riley had been arrested. “I love Riley, and this is a very difficult time in the cycle of joy and pain in parenting,” Clark wrote. “This will be evaluated by the legal system, and I am confident in that process.”

A right-wing news source hinted Riley’s behavior shows Clark to be a negligent parent or perhaps even a supporter of violent anti-police protests. My own feelings on this situation? I don’t think anyone should assume that Rep. Clark is a bad parent or that she approves of her daughter’s apparently lawless behavior. I know lots of parents who loved their children and directed them away from reckless behavior, but later, their children still did dangerous or dishonest things. Until there is solid evidence to the contrary, I’m going to give Rep. Clark the benefit of the doubt and assume she is one such parent.

During the Super Bowl, two Christian-themed ads promoting harmony, peace, and tolerance aired on TV. One ad stated at its conclusion “Jesus loves the people we hate.” While the messages themselves seemed unobjectionable, the Servant Foundation, the nonprofit group sponsoring the ads, came under attack for having ties to other groups that have opposed gay marriage and access to abortion. But there are two reasons why I’m inclined to give the foundation the benefit of the doubt and not pass judgment on them. First, the substance of their message is wholesome and sound, and second, I don’t know if the foundation’s leaders necessarily agree with all the policy positions taken by their supporters.

In conclusion, what am I saying here? That I agree with Rep. Clark’s political views? Not necessarily. But any disagreement I have with Rep. Clark stems from her position of public issues. With respect to her parenting, I give her the benefit of the doubt. Do I agree with the views of the people supporting the Servant Foundation? Maybe not, but I don’t hold the foundation accountable for the positions taken by their supporters.

The benefit of the doubt. Maybe we should all try that more often with the people with whom we disagree.