Devil in the Grove: A Review

Devil in the Grove: A Review

By: claycormany in Books

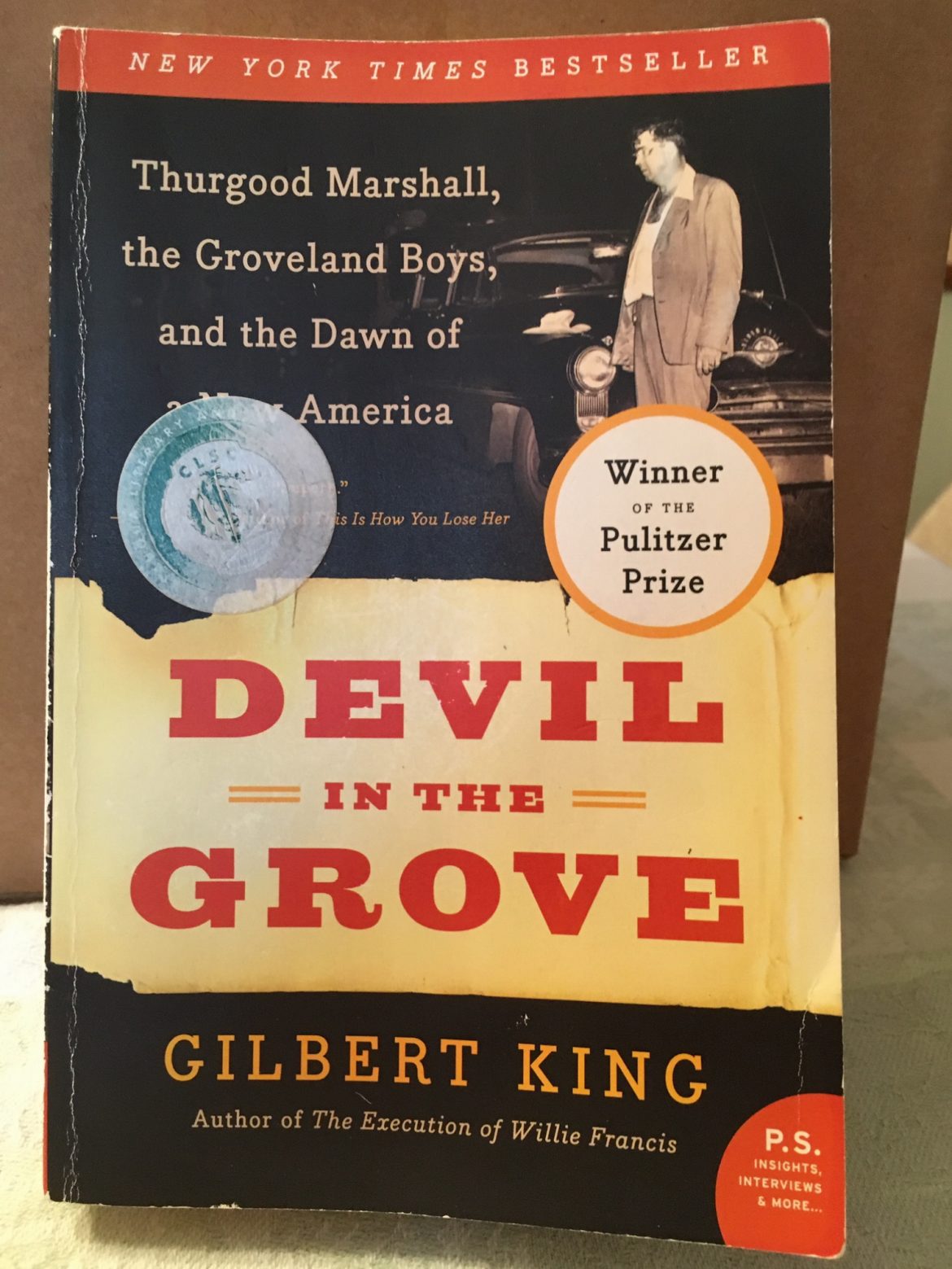

King, Gilbert. Devil in the Grove. New York: Harper Perennial, 2012.

As a child, I loved family vacations to Florida. Some of my happiest moments as a kid came while running through the waves at Daytona Beach and building sand castles under the glowing Florida sun. Little did I know there was a sadder, scarier, and menacing side to the Sunshine state. As I frolicked on the beach, black families struggled for existence under the weight of Jim Crow laws that put them at the mercy of racist sheriffs and Ku Klux Klan night-riders. In his book, Devil in the Grove, Gilbert King gives the reader a glimpse into this darker side of Florida. At the center of the story are four young black men, the “Groveland Boys” as they came to be known, accused of raping a 17-year-old white girl. On the night of July 15, 1949, two of them — Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin — stopped to help Willie Padgett and his wife Norma after their car broke down. By the following morning, Shepherd and Irvin were wanted by Lake County, Florida lawmen for allegedly beating up Willie and raping Norma. Also wanted for the same crime were two other young black men, Charles Greenlee and Ernest Thomas.

It was future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and his team of NAACP lawyers who came to the defense of the Groveland Boys. The early chapters of the book provide some context for the case. King shines a light on the 1946 Columbia, Tennessee race riot, which found Marshall winning acquittals for 23 blacks accused of multiple violent crimes, including attempted murder. King also provides insight to Marshall’s health problems (he was stricken with a mysterious pneumonia-like virus) and his interactions with people outside the courtroom, such as his mentor, Howard University law professor Charles Hamilton Houston, and NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White.

Marshall never hid the fact that trips into the South to defend black clients scared him. He found the image of lynch-victim Rubin Stacy to be particularly haunting. As King explains, “It wasn’t the indentation of the rope that had cut into the flesh below the dead man’s chin, or even the bullet holes riddling his body, that caused Marshall … to stir in his sleep. It was the virtually angelic faces of the white children, all of them dressed in their Sunday clothes, as they posed…in a semicircle around Rubin Stacy’s dangling corpse.”

King makes it clear that Marshall and his colleagues had good reason to be afraid when they headed to Lake County to defend the Groveland Boys. The biggest reason of all was Sheriff Willis McCall. With ties to the Ku Klux Klan, McCall was little more than a barbarian with a badge and a gun. Though he stopped an early attempt by local residents to lynch Shepherd and Irvin, McCall did not hesitate to threaten and physically abuse Shepherd, Irvin, and Greenlee (Thomas was never taken captive). Among other things, he allowed his deputies, James Yates and Leroy Campbell, to beat the three men with an iron rod encased in a hose. And when night-riding vigilantes burned down the homes of black families (including the home of Samuel Shepherd’s father) in Bay Lake, McCall made no effort to identify, much less arrest, the culprits. Once the Groveland Boys’ trial ended, however, McCall did find time to run Franklin Williams, the lead counsel for the defendants, out of Lake County in a high-speed car chase.

King does not spend too much time on the Groveland Boys’ trial itself, which is understandable since it didn’t take but a few days. The issue essentially came down to the word of Shepherd, Irvin, and Greenlee against that of Norma Padgett. Prosecutor Jesse Hunter had no medical evidence to verify that Norma had actually been raped. Moreover, his timeline of events was flawed, given that Greenlee was already in police custody for other reasons when the rape supposedly occurred. But it didn’t matter. Hunter knew that a jury comprised entirely of white men would never believe black men could be innocent if a white woman said they were guilty. The defense understood that, too. Accordingly they never argued Norma hadn’t been raped, only that she had mistakenly identified Shepherd, Irvin, and Greenlee as the rapists.

King adds color and life to his narrative by giving insights to the people who reported on the case or took part in it. Besides New York NAACP lawyer Franklin Williams, the defense team included Alex Ackerman, an Orlando trial attorney who at one time was the only Republican member of the Florida legislature. Judge Truman Futch, who whittled cedar sticks while listening to testimony, presided over the trial, while black journalists Ted Poston and Arnold DeMille reported on the proceedings for their respective newspapers, the New York Post and the Chicago Defender. Mabel Norris Reese, editor of the local Mount Dora Topic, may have been the most interesting person reporting on the case. A friend of Jesse Hunter’s, she started off convinced the Groveland Boys were guilty, but eventually realized they were innocent. Of all the people supporting the Groveland Boys, Harry T. Moore, president of the NAACP’s Florida branch, paid the highest price for his involvement. On Christmas night, 1951, his home in Mims, Florida was bombed with tragic results.

In the end, Devil in the Grove, is about much more than a trial. It’s about an ugly side of America in general and the South in particular that, sad to say, has not completely disappeared. At times, I believe King spends too much time on facts that are interesting but irrelevant to the Groveland Boys’ case. For example, he often discusses notable people who resided at the Harlem apartment building where Marshall lived. This proved to be a minor distraction. Even so, Devil in the Grove gives a portrait of America that is equally powerful and painful. And perhaps most painful of all is the fact that, though faded, this portrait still stares us in the face today.

Tags: Groveland, Lake County, NAACP, Thurgood Marshall, trial, Willis McCall