A Review of Profiles in Courage

A Review of Profiles in Courage

By: claycormany in Books

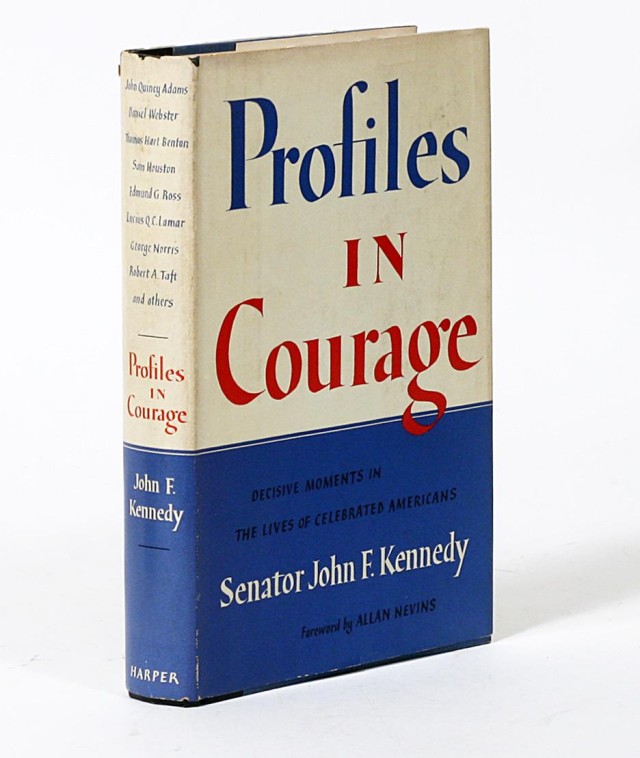

Kennedy, John F. Profiles in Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 1956.

Courage. The Bible commanded it. The Cowardly Lion wanted it. The Medal of Honor recognized it. And John F. Kennedy wrote about it in his 1955 Pulitzer Prize-winning book Profiles in Courage. JFK’s book focuses on eight U.S. Senators, serving at different periods of American history, who angered their constituents by following their consciences and taking an unpopular stand on an issue of national significance. Prior to analyzing the Senators, Kennedy provides some historical context for the actions they took. He also notes the changing role of the Senate itself. As conceived by the Founding Fathers, “the Senate was to be less of a legislative body… and more of an executive council, passing on appointments and treaties and generally advising the President, without public galleries or even a journal of its own proceedings.” But, Kennedy notes, “as it must to all legislative bodies, politics came to the United States Senate.”

Some of the eight Senators featured in Profiles, such as John Quincy Adams, are fairly well known. Others, like Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, are not. And despite differences in their party affiliations, priorities, and personalities, Kennedy believes they “held much in common… above all, a deep-seated belief in themselves, their integrity and the rightness of their cause.”

There is a two-fold benefit to reading about the eight Senators highlighted in Profiles. First, there’s the insight the reader gains into the lives of prominent American statesmen. Second, there’s the knowledge acquired about hotly debated issues that shaped the American political landscape of past decades. For example:

- John Quincy Adams displayed courage on at least two occasions. First, as the only Federalist to support the Louisiana Purchase and the $11 million to accomplish it, and second, for his support of the 1807 Embargo Bill against Great Britain, which created economic hardship throughout New England, especially in Adams’ home state of Massachusetts.

- Daniel Webster’s demonstration of courage came with his advocacy of the Compromise of 1850, which included a provision (much hated in New England) for strengthening the Fugitive Slave Law. For taking this stance, Webster was called a “fallen star” by Horace Mann, a “traitor to the cause of freedom” by William Seward, and “the most meanly and foolishly treacherous man I ever heard of” by James Russell Lowell.

- Edmund G. Ross of Kansas was a harsh critic of President Andrew Johnson. Yet, believing that “insufficient proofs” and “partisan considerations” lay behind Johnson’s impeachment, he courageously voted to acquit the President at his trial in 1868. Though the vote cost him his seat in the Senate, Ross later won praise for having “saved the country from… a strain that would have wrecked any other form of government.”

- Nebraskan George Norris showed courage first in opposing President Wilson’s Armed Ship Bill on the eve of World War I and then for crossing party lines to back Democrat Al Smith in the 1928 Presidential election. The latter move was particularly confounding and aggravating to Republicans, since Norris was a “dry,” that is, a proponent of Prohibition, while the “wet” Al Smith favored its repeal.

In a closing chapter, JFK notes other examples of political courage that occurred outside the Senate. John Adams’ legal defense of the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre stands out here. Kennedy also stresses a politician may display courage even when fighting for a wrong or misguided cause. “Surely in the United States of America, where brother once fought brother, we did not judge a man’s bravery under fire by examining the banner under which he fought.”

I enjoyed reading this book, even though Kennedy’s writing is a bit awkward at times. He has a tendency to compose overly long sentences that could be shortened or divided into two sentences for the sake of clarity. That said, I find it refreshing to see him admiring the courage of Robert Taft, a Republican, and identifying positive qualities even in men — like Sam Houston — who owned slaves. If today’s readers can overlook the politically incorrect language of JFK’s book (he freely uses generic masculine pronouns), they can learn much about courage both inside and outside of the Senate.

Tags: constituents, courage, profile, Senate, statesmen